On 8 October 1997, 70 Bavarian police officers raided an apartment in Munich belonging to a Turkish antiquities smuggler, Aydin Dikmen. Hidden behind false walls and double ceilings, they found a massive horde of religious artefacts most of which had been looted from the occupied part of Cyprus after 1974.

The discovery was the result of a sting, the largest European art trafficking sting since World War II, initiated and orchestrated by a remarkable Cypriot woman, Tasoula Hadjitofi, a refugee from Famagusta, successful entrepreneur and longtime honorary consul for Cyprus in The Hague.

The Icon Hunter is her powerful memoir in which she describes her mission to repatriate Cyprus’ lost treasures on behalf of the Church of Cyprus. It became her raison d’etre, a lifetime quest and her way of regaining justice for Cyprus and for what she herself had lost as a result of the Turkish invasion.

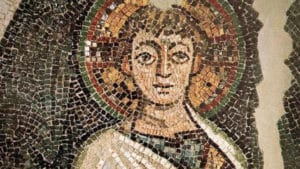

Tasoula was also behind the successful repatriation of the Kanakaria mosaics. She was the one who encouraged the late Archbishop Chrysostomos I to sue the American art dealer Peg Goldberg for their return which ended in a landmark court ruling for the global art trade. The mosaics were finally returned in 1991.

Together with the archbishop, who trusted her completely, she fought almost obsessively for the return of various religious items from Cyprus, often unsuccessfully as in the case of the ‘royal doors’ from the church of Peristerona, which was bought by the Kanazawa College of Art in Japan.

Her memoir tells how Michel Van Rijn, a notorious art dealer and middle man between Dikmen and art buyers, first made her aware in 1988 of the cultural cleansing that was occurring in Cyprus, when he tried to sell her information on Cyprus’ lost treasures. Having fallen out with Dikmen and fearing for his life, Van Rijn’s game was to turn informer and get Dikmen before Dikmen got him.

Art trafficking is big business. Estimated to be worth several billion dollars a year, it is third in profitability after illegal arms and drug trades. Not surprising that in her passion to protect Cyprus’ cultural heritage, not only did her business and family suffer, but Tasoula may also have been endangering her own life.

Pitting her wits against the dealers, she managed to find ways round loopholes in the law that had allowed them to legitimise the sale of illicit property. For example, when Cyprus wouldn’t invoke the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in the Event of Armed Conflict (the Hague Protocol), she tried to get Greece to invoke it instead in order to get the return of an icon stolen from the monastery of Antiphonitis which a Greek, who lived in Switzerland, had purchased from Sotheby’s. The church began a civil case against the Greek. No one thought to invoke the Hague Protocol. Tasoula persuaded the archbishop to contact the president of Greece and ask him to do so arguing how could Greece ask the British for the return of the Parthenon Marbles and yet deny invoking the protocol for Cyprus? Likewise, how can Cyprus ask for the protocol to be invoked to get back the artefacts in Holland, yet not demand the same of Greece?

In March 2013 Cyprus got back 173 artifacts from the Munich sting and two icons from another ongoing case. Another 34 artefacts were returned two years later. Sadly, 49 others had to be auctioned off because of insufficient proof of provenance, the result of disorganisation on the part of the church in documenting what they had and lack of communication between government departments.

As if fighting the dealers wasn’t enough, Tasoula also found herself up against petty Cypriot office politics. “Success has many fathers,” the archbishop told her, as government departments tried to take the credit for the sting. The delay they caused trying to sideline her and following wrong tactics meant the repatriation almost didn’t happen as the statute of limitations was running out.

After Cyprus joined the EU and opened an embassy in The Hague, she was summarily dismissed from honorary consul. She believes that this was because the new ambassador felt she overshadowed him. She continued to search for Cyprus’ treasures as the representative of the church, but gradually realised that she was not on the same page as the Cypriot authorities.

Tasoula’s purpose was to recover the artefacts and bring them home. The attorney-general’s purpose was to prosecute Dikmen. He wasted precious time trying to extradite Dikmen to Cyprus where he would have faced a maximum two-year sentence for theft, something that would have been difficult to prove. Instead Dikmen could have been prosecuted immediately in Germany where he faced a maximum 15-year sentence. They could have negotiated with him to release the artefacts to Cyprus in exchange for a lesser sentence, as Tasoula wanted.

The Icon Hunter describes how the attorney-general and his people foolishly made Van Rijn aware that they needed his testimony and cooperation in order to prosecute. Without documentation and proof of what Munich artefacts belonged to Cyprus, the stolen items could not be repatriated. Van Rijn was able to play them and ask for more and more money, getting them to turn against Tasoula, despite her repeated warnings that he was not to be trusted. Their actions almost caused the artefacts to be lost forever and is a sorry chapter on the state of affairs on our island.

When the artefacts were finally returned to Cyprus, 16 years after the sting, neither church (Archbishop Chrysostomos I had by then died) nor state invited her to welcome home what she had worked to achieve for almost 30 years.

Not willing to let her life’s work go to waste, she has since turned her attention globally, taking the lessons she learned from Cyprus and sharing them with the rest of the world.

She launched Cultural Crime Watchers Worldwide (CCWW) and set up Walk of Truth, a non-governmental organisation whose mission is to engage the public over the importance of protecting and preserving cultural heritage in areas of conflict and rallies legislators and politicians to strengthen laws around art trafficking.

Many of Cyprus’ treasures are still missing and may never surface. Unfortunately the exquisite mosaic of Saint Andreas from the Kanakaria church is amongst them. Chances of it ever being found are slim, especially as the statute of limitations is running out. True to form, Tasoula writes that she will not rest till she finds it and has made it a symbol of missing or looted works of art worldwide.

By Marina Christofides

Source: Cyprus Mail